Today is only yesterday's tomorrow

Жаль, что умер коллекционер, но если бы не это печальное обстоятельство - разве не появились бы в Сети его сокровища, выставленные на аукцион?

Всем Верна!

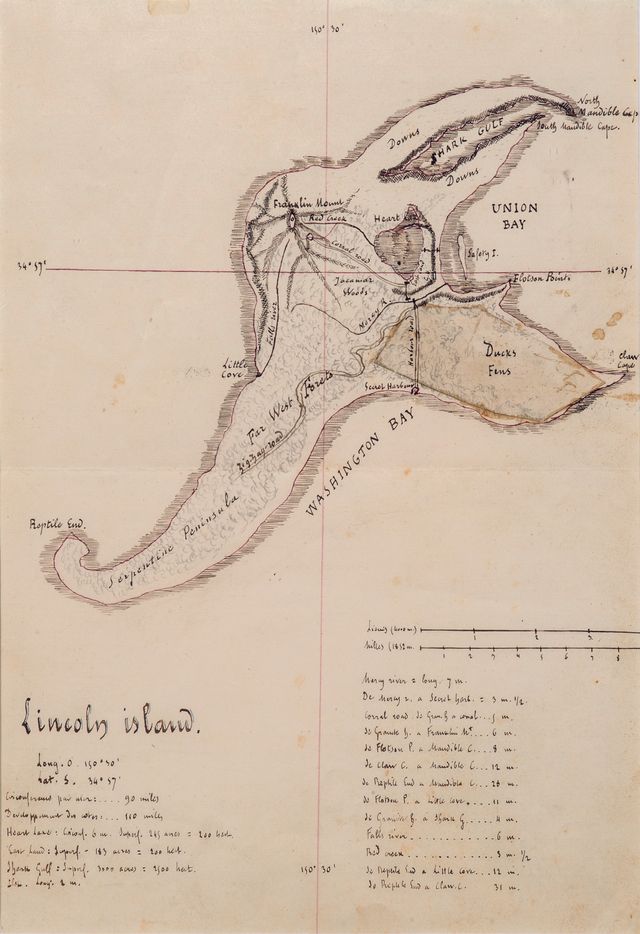

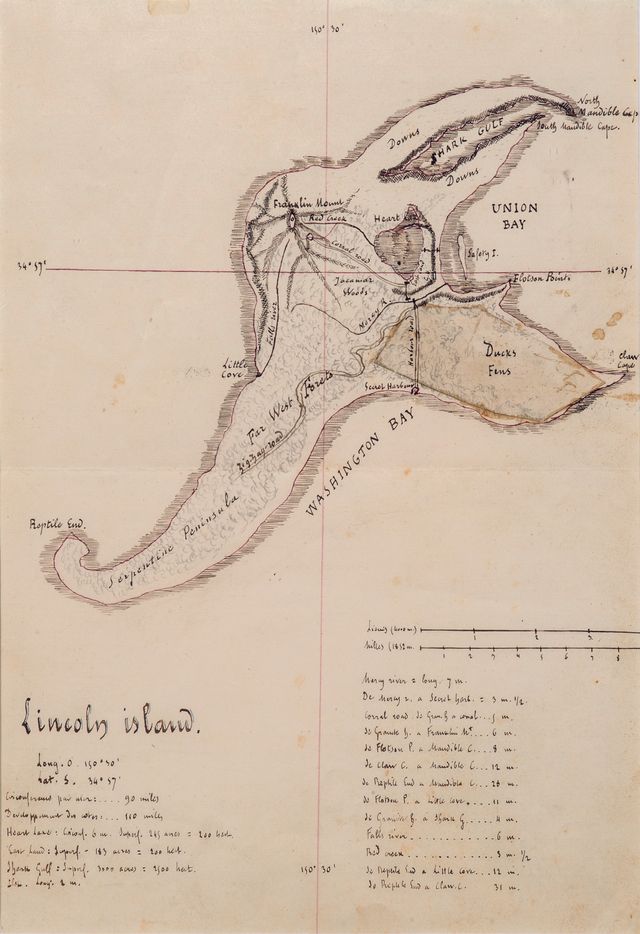

Ещё красотапростыня про картуMap drawn and inked by Jules Verne in 1874 showing Lincoln Island for L’île Mystérieuse / Corrected proof, annotated and signed by Jules Verne / Published final engraving.

The Mysterious Island, more so than Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea or Around the World in Eighty Days, is unanimously thought to be Jules Verne’s finest novel and the one in which his genius found its best expression. The work can be considered a culmination. And Lincoln Island, the last port of the Nautilus, Captain Nemo’s final refuge and then his sanctuary, is at once its setting and its starring character, whose anger we come to know. It is often in the islands that Jules Verne located his dreams and his utopias. And it also there that they disappear into the depths. The Mysterious Island is a key – not to say the key – to his entire work.

While nearly all the manuscripts of Jules Verne have been found and conserved, drawings by Verne can be counted on the fingers of one hand.

Do drawings by Jules Verne exist?... Nothing… or almost nothing that could be considered an artistic work and that one would be tempted to publish. A visionary like Jules Verne might have shown some proclivity for art. The same can be said of Victor Hugo, whom he admired. But the author was decidedly not an artist.

He produced nothing that can truly impress us … except for one map.

But what a map!

It was the only one he was to leave to us, the only major work still needed to crown his graphical heritage. “His” map of the Mysterious Island…

There could only be one major drawing of such force and inventiveness by the hand of Jules Verne. It is the one included in all good illustrated editions of the novel, both French and foreign.

And here is that drawing, in all its majesty.

The map is not only a unique document. It is imperial, not to say imperious. And more than that, it is miraculous. Why? Because no one expected it to exist, and because it seems to shine like a star at the summit of the pyramid of graphical remembrances of the author, the only one we would be tempted to select out of all the others – as if there could be a single one that could be compared to it.

What else could possibly be as spectacular, except for a plan of the Nautilus drawn by the author himself? And it is not a question of the sheer volume of paper, the number of pages covered by the author’s pen. It is a question of force. And this document has the force of an entire manuscript, if not a summation of his entire oeuvre.

But its importance also comes from the fact that it is also alive, overflowing not only with geographical information, but also other information that tells us about how his work evolved, and is not found either on the final map or in the narrative. It is much more elementary than the final map; it is a first draft. It is Jules Verne’s working document, an imaginary exploratory map he drew for his personal use, yet with the intention of sharing it with his readers and having it reproduced.

Seen in this way, it has the power of a codex.

Jules Verne imagined and then drew “his island” as he would have allowed no-one to else to draw it, as, ten years later, Robert Louis Stevenson – himself a reader and critical admirer of his works – was to do for his Treasure Island. More eloquent than the descriptions – one picture is worth a thousand words –, his map was as indispensable to him as his texts. With its help, he was able to dive again and again into his work and find his place again; it was the foundation for his imaginings and wanderings in building and directing his narrative.

The autograph map

The title, above the geographical indications: Lincoln Island (and not, in French, île Lincoln), done in black ink with fine round vertical characters which Jules Verne thickened with a fine blue border to create a slight relief effect.

The island, whose tortured shape and tentacle-like appendages suggest some fantastic cephalopod or bizarre crustacean, complete with claws – surely a sea-monster! Although some, accurately enough, see the shape of an elephant’s head. The author drew the contours in red ink and, in the heat of inspiration, detailed the topography, suggested relief using conventional hatchings, indicated areas of vegetation in light pencil (without inking), sketching the light undergrowth the engraver’s burin would make legible.

Verne drew with care, but without excessive preciseness, leaving no important details out. The pen-work is like Verne himself – showing much application, meticulous, almost the work of a miniaturist. Notice how tiny the lettering becomes – the careful calligraphy of an accountant accustomed to writing in small, cramped columns, reminding us that the author was once a stock-exchange employee. This is no mere summary sketch, but an already-detailed, clear drawing of the final map, one Verne intended for the engraver to reproduce in its essential lines, giving it cartographic credibility, specifying the contours of the coastlines (merely suggested by the author), enriching it with relief hatchings and the depth curves found in navigational charts.

An amusing detail: a paper patch applied by Jules Verne, doubtless to mask an inkblot or a too-vigorous erasure. On it, he wrote “Harbour Road,” and, legibly, “Ducks Fens.”

Only the place names were to change. And that is where things become interesting.

The map he imagined and drew is in English

From his earliest novels, Jules Verne had a soft spot for the Anglo-Saxons, and especially the English, who were highly enterprising travellers in the 19th century – Dr. Fergusson, Captain Hatteras, Phileas Fogg –, but whom he found to be stiff and cold despite their picturesqueness and quickly abandoned in favour of Americans – callow, warm-hearted adventurers in love with freedom.

The author himself admitted he had no mastery of English, but he loved the words and expressions that dot the atlases. They were an endless source of inspiration, and we find them here: Serpentine Peninsula, Little Cove, Claw Cap, Reptile End, Heart Lake, Franklin Mount, Union Bay, Shark Gulf, Mandible Cape, and so on.

Jules Verne wanted his map to be authentically Anglo-Saxon, but between his drawing and the final proofs, he gave up on that idea, doubtless at Hetzel’s request. The text of the novel was corrected. This is a discovery. What we are seeing here is the spontaneity of a first draft, none of which was to remain in the final version. All the names would change (Heart Lake became Lac Grant; Shark Gulf was changed to Marais des Tadornes) or be literally translated (Falls River became Rivière de la Chute) to make them more mnemonic for his French readers.

Newly discovered working notes

All the place names are still part of the drawing. None of them are written in the margin. The legends provide information and reference points on locations and distances not found on the final map. They served to avoid inconsistencies. With them, Verne was able to estimate the time necessary for his heroes’ many comings and goings and follow Cyrus Smith, Gedeon Spilett, Pencrofft, and Harbert in their travels through their kingdom, stopwatch in hand.

For example, we learn that the circumference of the island by sea is 90 miles, that the coastline covers 110 miles, and that the length of Mercy River is 7 miles.

The same details are given for Heart Lake (circumference: 6 miles; area: 100 hectares), East Land (200 hectares) and Shark Gulf (2,500 hectares). And for the îlot (?) (illegible), which must be Safety Islet (length: 2 miles).

Next are twelve distance lines from one point to another, meant to serve as a route guide, supported by a scale in leagues and in miles (Verne specifies the nautical mile, or 1,852 m).

The author’s conversion of acres to hectares, exact for Heart Lake, appears very doubtful in subsequent cases.

Longitude (150° 30’) and latitude (34° 57’) are already set down in degrees and minutes, but not in seconds. They were to remain unchanged.

But this extraordinary document is not isolated. It is accompanied by a second one, forming the complete dossier of the illustrations for the text published in the Magasin d’Education et de Récréation, then in the octavo edition of the novel:

– A proof, which we describe as “before the fact,” on which Jules Verne modifies and complements the legends in red ink, enabling us to track the evolution of his creative work.

– The final print added by Éric Weissenberg, from the Magasin d’Education et de Récréation.

We should point out that the hand-drawn map and the corrected proof were discovered together.

The corrected, complemented proof

We note that on the proof, the essential work has already been done. Seven legends, either translated or converted to French form, are found on it. All indications of size or distance have disappeared. All that remained for Verne was to add the final modifications, in red ink:

– Correction of an error: We can see that he crossed out Lac Grand and substituted Lac Grant.

– Graphical enrichments: Indiquer des arbres autour du lac sur les rives (“Show trees around the lake, on the shores”). He suggests them with small pen strokes.

– Elsewhere, he specifies a mineralogical characteristic: Basaltes (“basalt”) for the shoreline adjacent to Mount Franklin. Since it might have led to confusion, since the map otherwise had only topographical markings, that detail is not found on the final plate.

– Finally, Verne added seven legends, numbered 8 to 14: Crypte Dakkar (Dakkar Grotto), Pont de la Mercy (Mercy Bridge), Grotte des Dunes (Dunes Grotto), Huîtrière (Oyster-bed), Creek Glycerine (Glycerine Creek – “Glycerine” spelled in English, without the accent; the French acute accent was added to the final plate), Caverne des Jaguars (Jaguar Cavern), Gisements de houille et de fer (Coal and iron beds).

The longitude reading was set too high on the meridian. He scratched it out and rewrote it at the bottom of the engraving.

He requested a second proof, in duplicate, and signed J Verne.

It its authenticity, its universality, and its evocative power, this beautiful map of the Island – the most famous of all imaginary lands, along with that of Robinson Crusoe – cannot fail to move us. A pure product of its author’s mind, it possesses all the poetry of a childhood dream and is the sole illustration the creator felt the need to set down in his own hand to accompany his finest novel.

Éric Weissenberg showed it only to such rare connoisseurs as he felt were worthy to see it. He defended it and kept it under close guard, as the jealous husband of a much-coveted wife refuses even to allow her to appear in public, choosing not to reveal its existence in the publications of the Jules Verne Society or in his book on the author. As a result, it had never been heard of outside a small circle of initiates. It was his collector’s secret.

Considering the universal renown of its author, this unique remembrance is a document of worldwide interest, which needs no translation. The fortunate acquirer who takes possession of this Mysterious Island will show that he or she has understood, better than others have, its importance for the author himself as well as its value as symbol, which it will always have for readers around the globe.

The Verne family in Provins in 1861. Если вы понимаете, о чём я. Теперь мне очень хочется знать, в каком порядке были сняты эти фотографии.

The Verne family in Provins in 1861. Если вы понимаете, о чём я. Теперь мне очень хочется знать, в каком порядке были сняты эти фотографии.

кто гдеDebout, de gauche à droite :

Marie, la plus jeune des sœurs de Jules Verne, dite « le chou » /Anne Ducrest de Villeneuve, l’aînée des trois sœurs Verne /Alphonsine et Amélie Verne, tantes paternelles / Honorine Verne, veuve Morel, née Deviane, épouse de Jules Verne / Jules Verne / Sophie Verne, née Allotte de la Fuÿe, sa mère / Pierre Verne, son père / Antoinette Garcet, mère d’Henri Garcet, née Verne et tante paternelle de Jules Verne /Alphonse Garcet, fils d’Henri Garcet / Ange Ducrest de Villeneuve, époux d’Anne Verne / Henri Garcet, cousin germain de Jules Verne / Antoinette Garcet, son épouse.

Assises, de gauche à droite :

Masthie Prévost, grand-mère paternelle de Jules Verne, qui décédera la même année, âgée de 93 ans, qui connut l’Ancien Régime, ayant 22 ans en 1789 / Valentine Morel et, décalée en hauteur, Suzanne Morel, nées d’un premier mariage d’Honorine, et belles-filles de Jules Verne.

Oil painting of Jules Verne. Smiling portrait with a short grey beard.

Oil on canvas not signed and not dated (ca 1875). Framed.

Original photograph of Honorine Verne. Picture by Berthaud/Paris-Amiens. Dedication: “à sa nièce/souvenir/affectueux/H. Verne/1888”. (to my niece/with affectionate/memory/H. Verne/1888.)

Счастливый ребятёнок. The Flight to France given as a prize to a deserving student

The Flight to France given as a prize to a deserving student

Original print (18 x 24 cm) of a twelve year old child (looking very serious with the sun in his eyes), posing in a garden whilst leaning on two books with ribbons. He is holding a crown of laurels. No date (circa 1895). One can clearly see that the first of the two books is Jules Verne’s Le Chemin de France with “a steamer” binding.

Всем Верна!

Ещё красотапростыня про картуMap drawn and inked by Jules Verne in 1874 showing Lincoln Island for L’île Mystérieuse / Corrected proof, annotated and signed by Jules Verne / Published final engraving.

The Mysterious Island, more so than Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea or Around the World in Eighty Days, is unanimously thought to be Jules Verne’s finest novel and the one in which his genius found its best expression. The work can be considered a culmination. And Lincoln Island, the last port of the Nautilus, Captain Nemo’s final refuge and then his sanctuary, is at once its setting and its starring character, whose anger we come to know. It is often in the islands that Jules Verne located his dreams and his utopias. And it also there that they disappear into the depths. The Mysterious Island is a key – not to say the key – to his entire work.

While nearly all the manuscripts of Jules Verne have been found and conserved, drawings by Verne can be counted on the fingers of one hand.

Do drawings by Jules Verne exist?... Nothing… or almost nothing that could be considered an artistic work and that one would be tempted to publish. A visionary like Jules Verne might have shown some proclivity for art. The same can be said of Victor Hugo, whom he admired. But the author was decidedly not an artist.

He produced nothing that can truly impress us … except for one map.

But what a map!

It was the only one he was to leave to us, the only major work still needed to crown his graphical heritage. “His” map of the Mysterious Island…

There could only be one major drawing of such force and inventiveness by the hand of Jules Verne. It is the one included in all good illustrated editions of the novel, both French and foreign.

And here is that drawing, in all its majesty.

The map is not only a unique document. It is imperial, not to say imperious. And more than that, it is miraculous. Why? Because no one expected it to exist, and because it seems to shine like a star at the summit of the pyramid of graphical remembrances of the author, the only one we would be tempted to select out of all the others – as if there could be a single one that could be compared to it.

What else could possibly be as spectacular, except for a plan of the Nautilus drawn by the author himself? And it is not a question of the sheer volume of paper, the number of pages covered by the author’s pen. It is a question of force. And this document has the force of an entire manuscript, if not a summation of his entire oeuvre.

But its importance also comes from the fact that it is also alive, overflowing not only with geographical information, but also other information that tells us about how his work evolved, and is not found either on the final map or in the narrative. It is much more elementary than the final map; it is a first draft. It is Jules Verne’s working document, an imaginary exploratory map he drew for his personal use, yet with the intention of sharing it with his readers and having it reproduced.

Seen in this way, it has the power of a codex.

Jules Verne imagined and then drew “his island” as he would have allowed no-one to else to draw it, as, ten years later, Robert Louis Stevenson – himself a reader and critical admirer of his works – was to do for his Treasure Island. More eloquent than the descriptions – one picture is worth a thousand words –, his map was as indispensable to him as his texts. With its help, he was able to dive again and again into his work and find his place again; it was the foundation for his imaginings and wanderings in building and directing his narrative.

The autograph map

The title, above the geographical indications: Lincoln Island (and not, in French, île Lincoln), done in black ink with fine round vertical characters which Jules Verne thickened with a fine blue border to create a slight relief effect.

The island, whose tortured shape and tentacle-like appendages suggest some fantastic cephalopod or bizarre crustacean, complete with claws – surely a sea-monster! Although some, accurately enough, see the shape of an elephant’s head. The author drew the contours in red ink and, in the heat of inspiration, detailed the topography, suggested relief using conventional hatchings, indicated areas of vegetation in light pencil (without inking), sketching the light undergrowth the engraver’s burin would make legible.

Verne drew with care, but without excessive preciseness, leaving no important details out. The pen-work is like Verne himself – showing much application, meticulous, almost the work of a miniaturist. Notice how tiny the lettering becomes – the careful calligraphy of an accountant accustomed to writing in small, cramped columns, reminding us that the author was once a stock-exchange employee. This is no mere summary sketch, but an already-detailed, clear drawing of the final map, one Verne intended for the engraver to reproduce in its essential lines, giving it cartographic credibility, specifying the contours of the coastlines (merely suggested by the author), enriching it with relief hatchings and the depth curves found in navigational charts.

An amusing detail: a paper patch applied by Jules Verne, doubtless to mask an inkblot or a too-vigorous erasure. On it, he wrote “Harbour Road,” and, legibly, “Ducks Fens.”

Only the place names were to change. And that is where things become interesting.

The map he imagined and drew is in English

From his earliest novels, Jules Verne had a soft spot for the Anglo-Saxons, and especially the English, who were highly enterprising travellers in the 19th century – Dr. Fergusson, Captain Hatteras, Phileas Fogg –, but whom he found to be stiff and cold despite their picturesqueness and quickly abandoned in favour of Americans – callow, warm-hearted adventurers in love with freedom.

The author himself admitted he had no mastery of English, but he loved the words and expressions that dot the atlases. They were an endless source of inspiration, and we find them here: Serpentine Peninsula, Little Cove, Claw Cap, Reptile End, Heart Lake, Franklin Mount, Union Bay, Shark Gulf, Mandible Cape, and so on.

Jules Verne wanted his map to be authentically Anglo-Saxon, but between his drawing and the final proofs, he gave up on that idea, doubtless at Hetzel’s request. The text of the novel was corrected. This is a discovery. What we are seeing here is the spontaneity of a first draft, none of which was to remain in the final version. All the names would change (Heart Lake became Lac Grant; Shark Gulf was changed to Marais des Tadornes) or be literally translated (Falls River became Rivière de la Chute) to make them more mnemonic for his French readers.

Newly discovered working notes

All the place names are still part of the drawing. None of them are written in the margin. The legends provide information and reference points on locations and distances not found on the final map. They served to avoid inconsistencies. With them, Verne was able to estimate the time necessary for his heroes’ many comings and goings and follow Cyrus Smith, Gedeon Spilett, Pencrofft, and Harbert in their travels through their kingdom, stopwatch in hand.

For example, we learn that the circumference of the island by sea is 90 miles, that the coastline covers 110 miles, and that the length of Mercy River is 7 miles.

The same details are given for Heart Lake (circumference: 6 miles; area: 100 hectares), East Land (200 hectares) and Shark Gulf (2,500 hectares). And for the îlot (?) (illegible), which must be Safety Islet (length: 2 miles).

Next are twelve distance lines from one point to another, meant to serve as a route guide, supported by a scale in leagues and in miles (Verne specifies the nautical mile, or 1,852 m).

The author’s conversion of acres to hectares, exact for Heart Lake, appears very doubtful in subsequent cases.

Longitude (150° 30’) and latitude (34° 57’) are already set down in degrees and minutes, but not in seconds. They were to remain unchanged.

But this extraordinary document is not isolated. It is accompanied by a second one, forming the complete dossier of the illustrations for the text published in the Magasin d’Education et de Récréation, then in the octavo edition of the novel:

– A proof, which we describe as “before the fact,” on which Jules Verne modifies and complements the legends in red ink, enabling us to track the evolution of his creative work.

– The final print added by Éric Weissenberg, from the Magasin d’Education et de Récréation.

We should point out that the hand-drawn map and the corrected proof were discovered together.

The corrected, complemented proof

We note that on the proof, the essential work has already been done. Seven legends, either translated or converted to French form, are found on it. All indications of size or distance have disappeared. All that remained for Verne was to add the final modifications, in red ink:

– Correction of an error: We can see that he crossed out Lac Grand and substituted Lac Grant.

– Graphical enrichments: Indiquer des arbres autour du lac sur les rives (“Show trees around the lake, on the shores”). He suggests them with small pen strokes.

– Elsewhere, he specifies a mineralogical characteristic: Basaltes (“basalt”) for the shoreline adjacent to Mount Franklin. Since it might have led to confusion, since the map otherwise had only topographical markings, that detail is not found on the final plate.

– Finally, Verne added seven legends, numbered 8 to 14: Crypte Dakkar (Dakkar Grotto), Pont de la Mercy (Mercy Bridge), Grotte des Dunes (Dunes Grotto), Huîtrière (Oyster-bed), Creek Glycerine (Glycerine Creek – “Glycerine” spelled in English, without the accent; the French acute accent was added to the final plate), Caverne des Jaguars (Jaguar Cavern), Gisements de houille et de fer (Coal and iron beds).

The longitude reading was set too high on the meridian. He scratched it out and rewrote it at the bottom of the engraving.

He requested a second proof, in duplicate, and signed J Verne.

It its authenticity, its universality, and its evocative power, this beautiful map of the Island – the most famous of all imaginary lands, along with that of Robinson Crusoe – cannot fail to move us. A pure product of its author’s mind, it possesses all the poetry of a childhood dream and is the sole illustration the creator felt the need to set down in his own hand to accompany his finest novel.

Éric Weissenberg showed it only to such rare connoisseurs as he felt were worthy to see it. He defended it and kept it under close guard, as the jealous husband of a much-coveted wife refuses even to allow her to appear in public, choosing not to reveal its existence in the publications of the Jules Verne Society or in his book on the author. As a result, it had never been heard of outside a small circle of initiates. It was his collector’s secret.

Considering the universal renown of its author, this unique remembrance is a document of worldwide interest, which needs no translation. The fortunate acquirer who takes possession of this Mysterious Island will show that he or she has understood, better than others have, its importance for the author himself as well as its value as symbol, which it will always have for readers around the globe.

The Verne family in Provins in 1861. Если вы понимаете, о чём я. Теперь мне очень хочется знать, в каком порядке были сняты эти фотографии.

The Verne family in Provins in 1861. Если вы понимаете, о чём я. Теперь мне очень хочется знать, в каком порядке были сняты эти фотографии. кто гдеDebout, de gauche à droite :

Marie, la plus jeune des sœurs de Jules Verne, dite « le chou » /Anne Ducrest de Villeneuve, l’aînée des trois sœurs Verne /Alphonsine et Amélie Verne, tantes paternelles / Honorine Verne, veuve Morel, née Deviane, épouse de Jules Verne / Jules Verne / Sophie Verne, née Allotte de la Fuÿe, sa mère / Pierre Verne, son père / Antoinette Garcet, mère d’Henri Garcet, née Verne et tante paternelle de Jules Verne /Alphonse Garcet, fils d’Henri Garcet / Ange Ducrest de Villeneuve, époux d’Anne Verne / Henri Garcet, cousin germain de Jules Verne / Antoinette Garcet, son épouse.

Assises, de gauche à droite :

Masthie Prévost, grand-mère paternelle de Jules Verne, qui décédera la même année, âgée de 93 ans, qui connut l’Ancien Régime, ayant 22 ans en 1789 / Valentine Morel et, décalée en hauteur, Suzanne Morel, nées d’un premier mariage d’Honorine, et belles-filles de Jules Verne.

Oil painting of Jules Verne. Smiling portrait with a short grey beard.

Oil on canvas not signed and not dated (ca 1875). Framed.

Original photograph of Honorine Verne. Picture by Berthaud/Paris-Amiens. Dedication: “à sa nièce/souvenir/affectueux/H. Verne/1888”. (to my niece/with affectionate/memory/H. Verne/1888.)

Счастливый ребятёнок.

The Flight to France given as a prize to a deserving student

The Flight to France given as a prize to a deserving student Original print (18 x 24 cm) of a twelve year old child (looking very serious with the sun in his eyes), posing in a garden whilst leaning on two books with ribbons. He is holding a crown of laurels. No date (circa 1895). One can clearly see that the first of the two books is Jules Verne’s Le Chemin de France with “a steamer” binding.